The 8 am departure for our journey to my mom’s lake house in northern Wisconsin had passed. We finally pulled out of her suburban Chicago driveway hours later but just in time for an Egg McMuffin at the McDonald’s only a couple of blocks from her house. The muffin plus a hash brown patty were the very last cards I had available to play in order to persuade her to get in the car. I had exhausted my store of reasoning, demanding, cajoling, and it came down to bribery. Fine, I’ll take it.

At the time Mom was in her mid-nineties and had begun suffering overtly from dementia. In the preceding years she was the master of concealment. One can only hide so much for so long. Her small, deteriorating house was her foothold on reality and she clung to it with the tenacity of a badger hound. Unless one knew how much joy she’d derive from being ‘at the lake,’ one might think me cruel for pulling her away.

The morning of departure, to avoid leaving, she packed and unpacked a motley assortment of clothes at least four times. Mom’s closet was full of lovely clean t-shirts and shorts, sweaters and jackets that she refused to wear. She insisted instead on stained t-shirts with holes in unfortunate places. Today’s choice was a bright pink v-neck riddled with bleached-out splotches. In the end it didn’t matter. As we drove away from the McDonalds drive-up window she had already soiled the front of it with hash brown grease and ketchup. To convince Mom to change her shirt was out of the question.

The 6 hour drive always turned into 9 hours when Mom was riding shotgun. We had to stop at every ‘interesting’ place like the gas station with the enormous 10 foot tall black and white concrete holstein cow whose sole purpose was to get suckers like us off the road and into their store. Mom wandered the aisles amazed at such exotic items like Zagnut bars and toilet bowl cleaner.

Shortly after the cow we saw another McDonalds and pulled in. This time for a hot fudge sundae for her to wear. Even though these stops were tedious it was a respite of sorts from the same questions Mom asked me over and over for hours. “How far do we have to go? How long have we been gone? Where are we now? How many miles to the cottage? Where’s my wallet? Do I have my checkbook? Did I lock the front door?” My favorite, “Did you turn off the iron?” First of all, who irons anymore, and certainly not my mother. That deadly device magically disappeared along with the connection to the gas stove, and any other potentially incendiary pieces of equipment. So many ways to set a fire

Occasionally when she ceased asking questions Mom would get a somewhat dreamy look on her face and drift into a surreal soliloquy. One rather lengthy musing centered on cloud highways that in future days would be traversed by “special cars.” She was eerily convincing, looking up into the sky while waving her hands through the sunlight streaming down from her open window. “You see, the highways would move around with the wind,” more hand waving toward the heavens, “so when you drove them you would have to be careful and look down a lot so you wouldn’t end up far away from where you wanted to go.” She settled back in her seat for a few minutes with a perfectly satisfied look on her face. She knew what the future held.

When I went to throw out the plastic cup from her sundae at the next stop Mom wouldn’t let it go, clinging to it with a death grip repeating a litany I’d heard since childhood. “This could be useful.”

Both of my parents were first-generation Americans, born of Eastern European immigrants. Both were young adults during WWII. They lived through many fearful days, and a substantial amount of deprivation. They were grateful for the opportunity to work hard, and even more thankful for the little they had. Along the way, they, and I suspect an entire host of others influenced by the hardships of the times, learned to hang on to all material goods. No stranger to this philosophy was another of that generation, the mother of a friend of my husband. She was known to have a box in the garage neatly labelled, “Bits of string too short to keep.” The box was full.

I have carried on the ‘this could be useful’ tradition as if it were burned into my brain. And, come to think of it, it probably was. I learned well to, as my mother would say while leaning in and grimly staring into my eyes as if the Gettysburg address or the 10 commandments were about to proceed from her mouth, “Waste not, want not.” My mom had a way of screwing up her face into a pinched Grinch-like expression. She was scary, but the message came through and my current stacks of sturdy cardboard boxes and plastic containers back up my claim. They could be useful!

Messages from the past, delivered by the gods and goddesses, demons and torturers of our tender years. They stick. I can laugh about ‘this could be useful’ for the simple reason that I live in a time of recycling. Other messages are harder to shake.

My mom was no Mary Poppins. The nasty witch in Hansel and Gretel comes to mind. Along with the Grinch face came the finger waggling inches from my nose. I was told, “Stop talking crazy about the things you see.” Moving in closer came the clincher, “The men in the white coats are going to come and take you away.” I was terrified. Of course I believed every word. I was a kid. I internalized that there was something fundamentally wrong with me. I needed to keep quiet, hide, and never let anyone into my world. However, the ‘craziness’ continued in my private cocoon. I had a hearty friendship with my invisible friend Navi. I just never talked about her anymore. Effectively silenced … Messages.

Decades roll by. Lots of experience and therapy, all coming to the same conclusion. Mom was right. I am a little bit out of my mind as, I suspect, all imaginative, creative people are. We are the dreamers. We are painters of the unseen. We are the night listeners. We are the singers of songs and tellers of tales. We are what gives value to all the truly insane machinations of the lords and rulers of this world. We bring the ragged, the beautiful, the untold and deeply hidden into this wildly magnificent life.

After the exasperating trip in the car we finally made it to the lake. Then came another full day of unpacking and moving her clothes from drawer to drawer to orient herself in her surroundings. After that she settled into as happy a place as my mom could find. I saw her relax and laugh as she pulled up a sunfish or a perch which had been tempted by a long dangly worm she had me snare on the hook at end of her line. For a brief time the doors of her tortured cage opened. All too soon the heavy metal door would slam shut locking her away once again in a prison of fearful confusion.

Our trip was one of the last times Mom made it to the lake. She had some lucid moments when the clouds cleared and she truly remembered who I was and the events of her early life. I listened. We laughed. We drank some wine and ate Italian beef sandwiches at The House of Dogs. We sat on the dock and she threw a line in, “Just in case the big one comes by.” We raked up some leaves, listened to the loons, and had morning coffee at her little kitchen table.

What followed was the inevitable sale of her home, a room in a nursing home, and a bout with covid making visitation impossible. I got a call from the nurse at the home who kindly let me say my good-byes to Mom the night she passed. All I could say was, “I love you mom, and it’s OK, you can sleep now.”

Mom went out kicking, screaming, resisting and fighting her decline; behaviors she had practiced over a lifetime of dissatisfaction. As a young mother she terrorized me. As an elder she tormented her care givers, and even dangerously locked one in her basement. Mom battled with my sister while she was kindly removing her from her home before it fell down around her. In the main she left this life as she had lived it … discontented resistance.

However, Mom did soften a bit with grandchildren. Those innocent eyes must have penetrated the deteriorating walls of her internal fortifications. We even found a place of peace in what had been a challenging relationship. There were many times when I asked myself, “Why do I care?” My only answer was, “because she’s my mom.” In that space of acceptance between us, however brief, and however long it took to get there, something deep inside of me went quiet. Not silenced, but stilled.

I think it is true that in difficulty there is something valuable to be found, a gift of sorts though it may not be easy to uncover. I believe the silencing in my early years turned my energies inward and sprouted seeds of imagination and creativity that might not have germinated had I been less afraid.

There is a story of two children; one optimist, one pessimist. Both were given shovels and left in rooms filled with horse manure. One child complained, pouted, got angry and threw down the shovel. The other child started digging while saying, “With all this poop there’s gotta be a pony in here somewhere!”

In Death as in Life

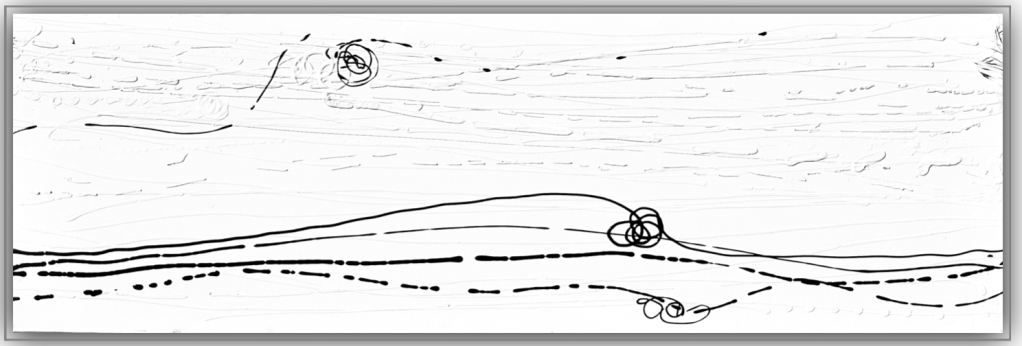

I painted In Death as in Life while reflecting on the ragged history with my mom and messages left behind. Black and white lines as distinct as life and death, yet they intertwine.